On February 21st, 1896, Judge Roy Bean made national headlines by promoting a unique boxing match. Robert James Fitzsimmons was to fight James J. Corbett, the heavyweight champion, but the Texas Legislature had outlawed boxing. While promoters sought a new location for the match, Corbett retired, handing the title to Irishman Peter Maher, who soon agreed to fight Fitzsimmons. Bean arranged for spectators and the press to travel by train from El Paso to Langtry, where he held the fight on a sandbar on Mexico’s side of the Rio Grande. Texas lawmen had no authority there and Mexico had no law enforcement on hand.

The desert along the Rio Grande looked especially ancient that morning. Canyon walls towered above the sparkling coil of the river. A cool winter breeze blew across the sandbar, carrying the smell of mud and horse sweat. The sun climbed quickly, illuminating a throng of spectators gathered around a makeshift boxing ring. They had travelled by train from El Paso to Langtry, and they were eagerly awaiting the contest.

John Walsh worked the crowd.

He moved easily among them, a lean man of twenty-five with dirty blonde hair, dust on his boots, and a practiced smile. He had learned at a young age that confidence was mostly a matter of posture and timing. Just short of a swagger, he told himself, because no likes a poser. A wide-brimmed hat shaded his face, and beneath his coat, pressing against his ribs, hung the leather satchel that held coins, bills, promissory slips, and the occasional gold watch. Anything that could be wagered. John’s hands were quick, his voice calm, and his gaze scanned for new prospects.

“Maher pays as long as a dry summer,” he told potential bettors. “Fitz is the favorite for sure, but Maher could surprise the world.”

He said it casually, like something he might not believe. That was the trick. Men trusted doubt more than certainty. Some of them laughed, shaking their heads. Others leaned in closer, smelling opportunity the way vultures smell death. Walsh gave Maher odds so generous that they bordered on insult, and the crowd responded exactly as he knew they would. Money flowed toward the underdog like water downhill, pooling fast and deep.

That was the plan, and Judge Roy Bean had calculated it perfectly.

Walsh had quickly learned about the judge’s shrewdness when he had drifted into Langtry at age nineteen, half-starved, riding a stolen mule whose ribs showed through its hide. Abandoned in Detroit at 12 years old, he had lived by his wits in the poor Irish neighborhood of Corktown. He sold matches and newspapers to survive, sleeping in whatever empty building or alcove he could find. Finally, with no prospects, he jumped a freight train heading west. He drifted between towns and jobs, often getting into trouble for theft. When he reached Langtry, he was at his lowest point, desperate for a new beginning.

He remembered the way the town first appeared to him, a cluster of buildings crouched in the desert along the Southern Pacific tracks, miles away from any other settlement. The Jersey Lilly Saloon stood at its center, leaning slightly. It was there that the legendary Roy Bean held court with his reputation as a “hanging judge.” He had famously called himself “the Only Law West of the Pecos,” a phrase the newspapers picked up and spread.

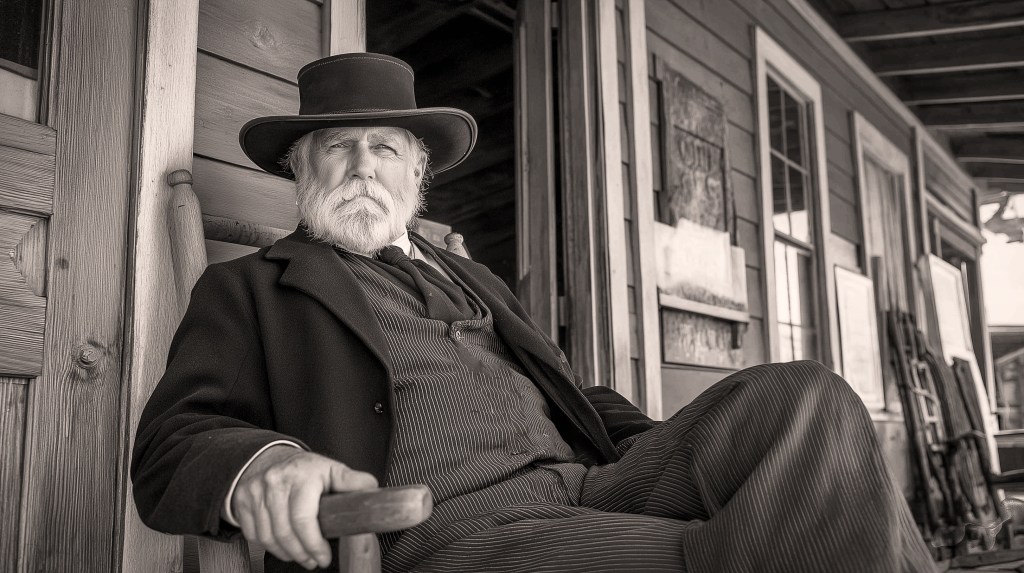

Bean had been sitting on the porch of the saloon that afternoon. He had a grizzled gray beard and a worn black Stetson perched on his head. There was a law book open on his lap, but even then, Walsh suspected it was more for show than reference. The judge watched the boy approach with the lazy interest of a man who had seen everything twice.

“You hungry, boy?” the judge had asked.

Walsh had nodded, too tired to lie, too proud to beg.

Bean fed him, then put him to work with the horses. He made it clear from the start: steal from me and I’ll hang you, steal for me and I’ll protect you. It wasn’t said cruelly or kindly. It was simply the truth, a verdict already reached.

Walsh mucked stalls until his arms ached and his back screamed. He hauled water under a Texas sun that seemed to burn him to the bone. He learned the smells of the stable and the moods of the horses. He also learned the rhythm of Langtry’s rough justice, listening from the doorway as Bean held court, watching men argue for their lives or their money under a mounted bear skin and a framed photograph of the famous English actress, Lillie Langtry.

Walsh never understood the judge’s infatuation with the British woman. He’d probably never meet her, and she certainly didn’t care about him. He claimed he had seen a photo of her in a magazine, and she embodied all his ideals of femininity and culture. Then again, since the town was named after George Langtry, an engineer who supervised Chinese labor for the railroad, maybe the judge just linked the last names in his mind. Either way, Walsh figured it was part of Bean’s calculated mystique, along with the “hanging judge” label even though he’d never executed a man.

Over time, Bean sent him on small errands, then longer ones with packages carried by horse to Del Rio, Uvalde, even San Antonio 200 miles away. Walsh knew that the bags could be sent by rail, and that Bean was simply testing him. A courier had to be trusted. He had to do what he was told and keep his mouth shut. Walsh learned which roads to avoid, which men to ride past without slowing, which questions not to ask.

He learned that reputation traveled faster than a horse, and that his was tied forever to Bean’s. People knew not to trouble John Walsh. If they did, they would answer to the Only Law West of the Pecos.

Now, standing amidst the spectators at the prizefight, the weight of the money satchel pulled at his shoulder, a physical reminder of how much trust rested on him, and how easily it could tip one way or another.

The crowd thickened as the hour approached. Sportswriters in stiff collars jotted notes, already shaping tomorrow’s headlines. Gamblers argued odds until their voices grew raw. Somewhere upriver, Texas Rangers fumed, unable to touch what happened on Mexican sand. Bean had chosen the place perfectly. It was just across the border and out of reach. He knew that Mexican authorities, if they even cared to come, would be delayed by distance in this remote stretch of the desert.

Walsh finished a final transaction with a cattleman from El Paso, then stepped aside to count. The sum dwarfed anything he’d ever carried. Enough to disappear, to buy land and anonymity.

That very thought had been creeping into his mind for weeks. Roy Bean treated him well, but Walsh knew the truth. He was a useful thing. Trusted, yes. Protected, yes. But loved? Maybe, in Bean’s rough way, but Walsh knew he would always be subservient, an extension of another man’s will. It had been grating on him.

Suddenly, the fighters entered the ring to a roar that echoed off the canyon walls. Fitzsimmons looked calm, coiled like wire, his eyes steady. Maher, broader and heavier, was already soaked in sweat, perhaps aware that he carried the hopes of every longshot gambler in the crowd. Walsh felt a flicker of sympathy for the fellow Irishman.

The bell rang and people began shouting encouragement to their favored fighters.

95 seconds later it was over.

Fitzsimmons’ rock-hard punch landed clean under Maher’s jaw, collapsing him like a toppled statue, his head hitting the packed sand with a finality that quieted the crowd for an instant. Fitzsimmons stepped back, his arms raised in triumph, while Maher remained motionless on the ground.

Then chaos erupted. “This fight was rigged!” yelled the gamblers who’d believed in miracles. Others jeered, some cursed, and some stared as if they’d just awoken from a dream.

Walsh stood still, watching a medic kneel beside Maher. Even though Bean had just hit the jackpot, disappointment washed through him. After all the maneuvering, bribing, and scheming to organize the fight, it had ended as suddenly as a candle snuffed out by a gust of wind. That was the world in a nutshell, Walsh thought.

By late afternoon, he’d finished collecting all the wagers, invoking Bean’s name to men who were reluctant to pay. The satchel was almost obscene with its weight. Bean would be richer than ever. Langtry would buzz for years on this event alone. The judge’s legend would grow, fed by exaggeration and envy, while Walsh would remain a footnote.

He mounted his horse as the sun dipped west. But instead of riding north towards Langtry, he headed south. No one stopped him. Why would they? He was Judge Bean’s man.

He rode along the river, keeping to the low ground where tracks were more concealed. The farther he went, the more the satchel spoke to him. Not with words but with possibility. Each mile put distance between the life he’d been given and the one he had decided to claim for himself.

By nightfall he reached Boquillas del Carmen, a small village clinging to the banks on the Mexican side. He paid cash for a room without giving his name. Its walls were bare, its bed narrow, and it smelled heavily of dust. Walsh barred the door with his saddle, then sat on the mattress and untied the satchel, spreading out its contents. It was more money than he’d expected. With this, he could vanish into Mexico and be nobody’s man but his own.

He lay down with the bag under his head, one arm looped through the strap, telling himself he would sleep lightly and awaken at the slightest sound. But he was restless, surprised at how much his conscience bothered him. He told himself that what he’d done was no different than what Bean had done all his life. He was just seizing his chance when it came. Then he recalled a quote from Mark Twain he’d heard a man once tell him: “A clear conscience is the sure sign of a bad memory.”

He tossed and turned until sleep descended harder than he expected.

He dreamed of the Rio Grande rising without warning and washing everything away. All the money and players, the boxing ring, even the border itself. Then he dreamed of Judge Bean sitting in his chair without a face, the law book open to blank pages.

He was torn from sleep as the door to his room burst inward. Rough hands seized him. He reached for the satchel by instinct, even as someone twisted his arm behind him.

“Don’t,” one of them said quietly. “Ain’t no call for that.”

Walsh recognized all three men as Bean’s employees. He had worked alongside them and ridden with them. They didn’t strike him or curse at him. They simply moved with the quiet efficiency of men following orders.

They rode north under a full moon. Walsh watched the silvery river slide past and thought about how close he’d come. Another hour, another day, another hundred miles south, and he might have outrun his old life. The men didn’t speak to him, giving no explanations. They didn’t have to. Langtry pulled at them like gravity. Judge Bean always knew where his people were. That was the real law, a presence that followed you even when you tried to cross a border.

Langtry seemed smaller in the early light of dawn. The Jersey Lilly leaned the same way it always had, like it might collapse any minute. Bean sat inside at his massive mahogany desk, his law book closed, his reading glasses low on his nose. The men brought Walsh to stand before him, then laid the satchel open on the desk, its riches spilling out as if it were a cornucopia.

For a moment, Walsh considered speaking up for himself. He would lay out the justification he’d rehearsed on the ride back. A man only gets so many chances; he must seize them when he can. Surely the wily old man would understand that brand of conniving. But as he looked at the judge, it all drained away. This was the man who’d fed him, trusted him, and pulled him up from rock bottom.

“I’m sorry,” Walsh said quietly. “I have no real excuse. I just fell prey to some grand dreams I’ve never had before. I’ll take whatever punishment you see fit. Even hanging. I deserve it.”

He waited for the sentence. He waited for the rope.

Bean studied him for a long time. The room was silent except for the distant nickering of horses.

Finally, the judge spoke.

“Go muck the stalls.”

Walsh blinked.

“You heard me,” Bean said. “You’re starting over. And I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to trust you again. Just get your ass back to work.”

That was it. No lecture. No sentence. No gallows.

Walsh felt weak with relief. Shame burned hot in his chest, but beneath it ran something else. A gratitude that was both fierce and painful. He turned and walked out toward the stables, the sun rising behind him, the desert still ancient and indifferent.

The stable door creaked as he pushed it open. The familiar smell embraced him, a mixture of manure, hay, and warm animal breath. Horses shifted in their stalls, their ears flicking, their eyes rolling toward him with the dim patience of creatures who understood work and routine but not ambition.

He took up a shovel and began his toil, sweat gathering quickly. As he worked, he felt something settle inside him, a kind of grounding. This was how he had begun, by doing what was set before him and doing it well. No matter how long it took, he vowed to return to a place of respect, if not in Bean’s eyes, at least in his own.

Outside, Langtry continued to awaken. A door opened. A voice called out. Somewhere up the hill, Judge Roy Bean took his morning coffee and sat on the porch of his saloon, the world lining up before him as it always did.

Walsh kept shoveling until any thoughts of what lay ahead disappeared. The future could wait. Right now, there was only the task before him. Right now, there was still breath in his lungs.

Simply being here and working was a grace he hadn’t earned.